|

III. RIOT AND LIBERTIES MASTERLESS MEN For all their fear of treason, rebellion, and sedition among the great, the Elizabethan authorities were equally frightened by disorder welling up among the multitude, that class of men and women that "have neither voice nor authority in the commonwealth, but are to be ruled and not to rule other[s]." William Harrison, whose Description of England appeared at the beginning of Holinshed's Chronicles, lumps everyone who works for a living, rather than living off of profits or capital, into this class. But his real preoccupation is with a small class of "masterless men," an emerging London underclass of homeless, thieves, and whores whom the authorities feared threatened the very fabric of respectable society. |

| |||

Thieves, whores, and the homeless had always been present in London—ordinances governing the brothels in London date from the early twelfth century, when the Bishop of Winchester grew rich from licensing and supervising them—but conditions in the fifteen-nineties conspired to increase the sense of menace. From 1592 to 1594 London was gripped by a devastating outbreak of plague. Upwards of ten per cent of the population died, and thousands more fled the terrified city. Thomas Nashe's "Litany in Time of Plague," performed for the archbishop of Canterbury in 1592, captures that terror: Gold cannot buy you health; Physic himself must fade; All things to end are made; The plague full swift goes by: Lord, have mercy on us! |

| |||

|

| ||||

|

THE LIBERTIES

|

| |||

A 1596 Order by the Privy Council to the Justices of the Peace of Middlesex describes how the liberties appeared to the authorities: a great number of dissolute, loose and insolent people harbored and maintained in such and like noisome and disorderly houses, as namely poor cottages and habitations of beggars and people without trade, stables, inns, alehouses, taverns, garden houses converted to dwellings, ordinaries [places serving food], dicing houses, bowling allies and brothel houses. The most part of which pestering those parts of the city with disorder and uncleanness are either apt to breed contagion and sickness, or otherwise serve for the resort and refuge of masterless men and other idle and evil disposed persons, and are the cause of cozenages, thefts, and other dishonest conversation and may also be used to cover dangerous practices. |

| >

|||

|

The Liberties were on the margins of the city geographically and culturally. Freed from the jurisdiction of the city fathers, the Liberties attracted those marginal pursuits and desires without a place in the regimented and regulated city: the gaming houses, taverns, bear-baiting pits, brothels, and, not incidentally, Shakespeare's theater. Here the city quarantined—but also permitted—those anarchic pursuits of pleasure. |

| |||

|

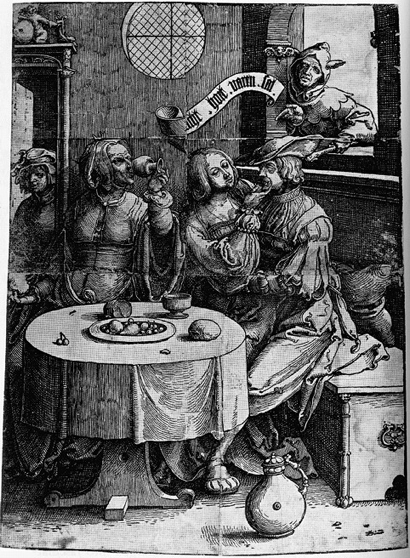

The authorities feared that such masterless men, stirring up rebellion, were a threat to the state and tried to whip them back to the parishes they left. In 1596 the aldermen appointed a marshal to round up "all manner of rogues, beggars, idle and vagrant persons within the borough of Southwark and the liberties thereof." Their fears of a vast criminal enterprise were fanned by writers of the so-called cony-catching pamphlets—"conies" or rabbits were the con man's marks—who described a burgeoning underworld of cutpurses, pickpockets, con men, thieves, and fences who spoke a colorful thieves' cant. |

||||

|

ROBERT GREENE, A NOTABLE DISCOVERY OF COZENAGE (1591) A Table of the Words of Art Used in the Effecting These Base Villainies, Wherein is Discovered the Nature of Every Term, Being Proper to None But to the Professors Thereof 1. High Law: robbing by the highway side. 2. Sacking Law: lechery. 3. Cheating Law: play at false dice. 4. Cross-Biting Law: cozenage by whores. These are the eight laws of villainy, leading the high way to infamy: In High Law: The thief is called a high lawyer. He that setteth the watch, a scripper. He that standeth to watch, an oak. He that is robbed, the martin. When he yieldeth, stooping. In Sacking Law: The bawd, if it be a woman, a pander. The bawd, if a man, an apple squire. The whore, a commodity. The whorehouse, a trugging place. In Cheating Law: Pardon me, gentlemen, for although no man could better than myself discover this law and his terms and the name of their cheats, barred dice, flats, forgers, langrets, gourds, demies, and many others, with their nature, and the crosses and contraries to them upon advantage, yet for some special reasons herein I will be silent. In Cross-Biting Law: The whore, the traffic. The man that is brought in, the simpler. The villains that take them, the cross- biters.

|

|

|||

|

These pamphlets, and these fears, leave their mark on the Boar's Head and Gadshill scenes in I Henry IV, with their band of "Diana's foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon" (1.2.23–4) and "Saint Nicholas' clerks" (2.1.59–60). "The thief that commits the robbery, and is chief clerk to Saint Nicholas," Thomas Dekker wrote, "is called the 'High Lawyer.'" |

||||

|

ALEHOUSE AND WHOREHOUSE This moral panic spread to the supposed haunts, the "very nurseries and breeding-places," of the underclass, the alehouses and the brothels, called stews. Puritan preachers took to their pulpits to denounce these "nests of Satan." To the civil authorities the alehouses fostered rebellion against religion and the realm. "When the drunkard," John Downame cried, "is seated upon the ale-bench and has got himself between the cup and the wall, he presently becomes a reprover of magistrates, a controller of the state, a murmurer and repiner against the best established government."

The Puritan Philip Stubbes denounced the alehouses in his Anatomy of Abuses as "the slaughter houses, the shambles, the blockhouses of the Devil, wherein he butchereth Christen men's souls, infinite ways, God knoweth." The alehouses and taverns also fostered prostitution; especially after the stews were outlawed in 1546, the bawds and whores took their trade indoors, like Pompey in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, a pander masquerading as a tapster. "Every tapster in one blind tavern or other is tenant at will [a tenant who holds a lease at the will or pleasure of the lessor], to which she [the whore] tolleth [acts as a decoy] resort, and plays the stale [prostitute used as a decoy] to utter [hawk, sell] their victuals," Stephen Gosson wrote in The School of Abuse (1579). "There is she so entreated with words, and received with courtesy, that every back room in the house is at her commandment." Despite proclamations closing the stews, the suburbs still boasted of over a hundred of them. Thomas Nashe's denunciation of them captures his horrid fascination. |

| |||

|

THOMAS NASHE, CHRIST'S TEARS OVER JERUSALEM (1592) London, what are thy suburbs but licensed stews? Can it be so many brothel houses of salary sensuality and six-penny whoredom (the next door to the magistrate's) should be set up and maintained, if bribes did not bestir them? I accuse none, but certainly justice somewhere is corrupted. Whole hospitals of ten-times-a-day dishonested strumpets have we cloistered together. Night and day the entrance unto them is as free as to a tavern. Not one of them but hath a hundred retainers. Prentices and poor servants they encourage to rob their masters. Gentlemen's purses and pockets they win dive into and pick, even whiles they are dallying with them. |

|

|||

|

No Smithfield ruffianly swashbuckler will come off with such harsh hellraking oaths as they. Every one of them is a gentlewoman, and either the wife of two husbands, or a bed-wedded bride before she was ten years old. The speech-shunning sores, and sight-irking botches of their unsatiate intemperance, they will I unblushingly lay forth, and jestingly brag of, wherever they haunt. To church they never repair. Not in all their whole life would they hear of God, if it were not for their huge swearing and forswearing by him. . . . |

|

|||

|

Great cunning do they ascribe to their art, as the discerning (by the very countenance) a man that hath crowns in his purse; the fine closing in with the next justice or alderman's deputy of the ward; the winning love of neighbors round about, to repel violence, if haply their houses should be environed or any in them prove unruly (being pilled and polled [stripped, shaved, or fleeced] too unconscionably). They forecast [scout] for back doors to come in and out by undiscovered. Sliding windows also, and trap boards in floors, to hide whores behind and under, with false counterfeit panes in walls, to be opened and shut like a wicket [gate]. Some one gentleman generally acquainted [having many friends], they give his admission unto sans fee, and free privilege thenceforward in their nunnery, to procure them frequentance. Awake your wits, grave authorized law-distributors, and show yourselves as insinuative subtle, in smoking this city-sodoming trade out of his starting-holes, as the professors of it are in underpropping it. . . . |

|

|||

|

Monstrous creatures are they, marvel is it fire from heaven consumes not London, as long as they are in it. A thousand parts better were it to have public stews than to let them keep private stews as they do. The world would count me the most licentiate loose strayer under heaven, if I should unrip but half so much of their venereal machiavellism [sexual deceitfulness] as I have looked into. We have not English words enough to unfold it. Positions and instructions have they to make their whores a hundred times more whorish and treacherous than their own wicked affects [inclinations] (resigned to the devil's disposing) can make them. Waters and receipts [drinks and recipes; medicines] have they to enable a man to the act after he is spent, dormative potions to procure deadly sleep, that when the hackney [hired woman] he hath paid for lies by him, he may have no power to deal with her, but she may steal from him, whiles he is in his deep memento [reverie or doze], and make her gain of three or four other [customers]. |

"Their whores |

|||

|

Nashe's "six-penny whoredom" and "ten-times-a-day dishonested strumpets" represent one end of the spectrum of prostitution in the Liberties. The other was represented by Holland's Leaguer, the most exclusive and expensive of the stews. Located in an old manor house among the bear-baiting pits in Paris Garden, Holland's Leaguer was designed as a fortress, surrounded by a moat spanned by a drawbridge leading to a studded door with a peep-hole guarded by a halberdier brandishing a battle-ax. In December, 1631, and January 1632, its staff fought off a siege by City authorities trying to summon its mistress, Bess Holland, to the court of High Commission, the highest and most powerful of the "bawdy" courts administered by the Church to punish vice. |

| |||

|

THE THEATRES IN THE LIBERTIES Amid the stews and taverns, the bear- and bull-baiting pits, among the licensed evils and quarantined pleasures of the Liberties stood London's theaters. Like the cutpurses and bawds, the whores and masterless artisans, the theaters gravitated to the Liberties to escape the stern regulation of the City fathers. When the City began to regulate the yards of inns in which the strolling players had been staging their plays, James Burbage built the first Theater outside its jurisdiction, in the suburbs, in 1576. It was followed by the Curtain in 1577. "Houses of purpose built . . . and that without the Liberties," as John Stockwood preached in 1578, "as who would say, 'There, let them say what they will say, we will play.'" By 1579, Stephen Gosson, himself a failed playwright, attacked the theaters for fostering prostitution: |

|

|||

|

STEPHEN GOSSON, THE SCHOOL OF ABUSE (1579) These pretty rabbits [whores]. . . that lack customers all the week, either because their haunt is unknown, or the constables and officers of their parish watch them so narrowly that they dare not queatch [utter a sound, i.e., implying complete submission]. To celebrate the Sabbath, [they] flock to theaters, and there keep a general market of bawdry. . . . every wanton and his paramour, every man and his mistress, every John and his Joan, every knave and his quean [whore], are there first acquainted and cheapen [haggle over the price of] the merchandise in that place, which they pay for elsewhere as they can agree. |

"Theatres keep |

|||

|

The city became surrounded by playhouses. The Liberties south of the Thames became host to the Rose (1587), the Swan (c. 1595), the Globe (fashioned from timbers of the original Theater by Shakespeare's company when their lease on the land expired in 1599), and the Fortune (1600). The City fathers also came to regard the theaters as sinks of iniquity, linking them not just with prostitution but sedition as well. In 1592 the Lord Mayor wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury complaining that "the daily and disorderly exercise of a number of players and playing houses erected within this city" were corrupting the youth "by reason of the wanton and profane devices represented on the stages." "To which places," he added, "also do usually resort great numbers of light and lewd disposed persons, as harlots, cutpurses, cozeners, pilferers, and such like; and there, under the color of resort to those places to hear plays, devise diverse evil and ungodly matches, confederacies, and conspiracies." |

|

|||

|

The theaters were felt to be a subversive institution, linked by proximity and ideological function to the forbidden pleasures of the Liberties. the players were marginalized by civic authority but served at the royal pleasure, wearing the livery first of the Lord Chamberlain and Lord Admiral and then of the royal family. In the Liberties the theater found itself at liberty to experiment with forms and ideas without precedent in English society. |

||||

|

RIOT AND THE LIBERTIES IN HENRY IV One of those experiments is on view in the two parts of Henry IV. In Richard II politics is waged by the grfeat aristocrats. Although the play challenges Richard's mystical view of the sources of power with a more material one, demonstrating that the angels which determine the outcome of any struggle for power are not God's angels but the coins that must fill the King's exchequer, Shakespeare recognizes the power of the myth of legitimacy, the ideology of divine right, in enforcing obedience and policing the state. Unless the realm consents to be ruled, it cannot be ruled, as Richard's fall demonstrates. And the ideology of divine right is a powerful weapon in winning that consent, as Elizabeth's ministers recognized in promulgating the "Homily against Disobedience" to answer the Pope's call to overthrow her. But in Richard II the king cannot reign without the support of the commons as well as the lords. Richard himself recognizes how Bolingbroke's "courtship to the common people" (1.4.24) makes him a threat to Richard's crown. York grants them a kind of parity with the barons: |

||||

|

And Richard concedes defeat when Scroop reports that the entire realm has risen against him: |

|

|||

|

However, in Richard II,the commons remain off stage, a disembodied force.

Besides the emblematic gardeners, the only commoner who speaks is the poor groom of Richard's stable, still loyal to his king. But in the two parts of Henry IV, |

||||

|

For there, they say, he daily doth frequent, With unrestrained loose companions, Even such, they say, as stand in narrow lanes And beat our watch and rob our passengers, Which he, young wanton and effeminate boy, Takes on the point of honor to support So dissolute a crew. |

||||

|

The prodigal prince haunts an urban demi-monde of taverns and stews, consorting with cutpurses and whores, assaulting the law itself on the king's highway in defiance of patriarchal order. Allegorically he embodies the figure of Youth from the moralities, misled by the Vice into a dissolute life of sensual excess set within a tavern, a link that Hal himself makes explicit when, impersonating his father the King, he calls Falstaff "that reverend vice, that grey iniquity, that father ruffian, that vanity in years" and "that villainous abominable misleader of youth, that old white-bearded Satan" (I Henry IV 2.2.431–2,462). But he represents as well the threat of riot and disorder not only from within Bullingbrook's own blood, but more generally of rebellion from beneath, from the class of masterless men who have neither voice nor authority but threaten to shake off the yoke of rule. While Mistress Quickly's alehouse is nominally located in Eastcheap, the center of London's butchers and cookshops and fit locale for Falstaff, a character whose epithets—"Call in ribs, call in Tallow" (I Henry IV 2.4.106)—link his great girth to his insatiable appetites, the world of the plays is that of the Liberties. |

| |||

|

Shakespeare draws as well on the growth of an underworld within the Liberties surrounding the theaters in which these plays were performed. Hotspur explicitly links the prince with that misrule for which the suburbs were notorious: "Never did I hear / Of any prince so wild a liberty" (I Henry IV 5.2.70–1). In the two parts of Henry IV, that underworld of alehouses and whorehouses, bawds and cutpurses that physically surrounded Shakespeare's playhouse enters the world of the plays, where it threatens the very order of the state. It represents the fear that a challenge to the ideology of divine right, represented within the play by the crown's loss of legitimacy, Henry IV's status as usurper and murderer of the lord's anointed, will so weaken the state that it will no longer wield the power to uphold the rule of law. And Shakespeare draws on an association in his own times between the assault on "the rusty curb of old father antic the Law" (I Henry IV 1.2.56) and the authorities' fear of a new lawlessness breaking out in the Liberties where Shakespeare's theater stood. |

"So wild a liberty" |