|

II. OBEDIENCE AND RESISTANCE Just as monarch and subject strove for sovereignty, so political thinkers debated the questions of authority and obedience, rebellion and resistance. How they thought about the state and its subjects was inextricably linked with their ideas about religion. The Renaissance inherited from the Middle Ages an assumption that monarchs derived their authority from God. In the Old Testament kings reign by divine ordination. "He changeth the times & seasons: he taketh away kings: he setteth up kings," Daniel explains to the Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar (2:21); "the most High hath power over the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will, and appointeth over it the most abject among men" (4:17). "Thou shalt make him King over thee, whom the Lord thy God shall choose," God decrees in Deuteronomy 17:15. "I will set up thy seed after thee, which shall proceed out of thy body, and will stablish his kingdom," God promises David in Samuel 7; "And thine house shall be stablished and thy kingdom for ever before thee." "Thus sayth the Lord God of Israel, I anointed thee King over Israel," reads 2 Samuel 12:7. In Proverbs 8:15, the Lord says, "By me, Kings reign, and princes decree justice." "Whereby," the translators of the Geneva version explain in their commentary, "he declareth that honors, dignity or riches come not of man's wisdom or industry, but by the providence of God."

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Of Obedience to the rulers, who bear not the sword in vain:

1 Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers: For there is no power but of God. The powers that be, are ordained of God. 2 Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: And they that resist, shall receive to themselves condemnation. 3 For magistrates are not feared for good works, but for evil. Wilt thou then be without fear of the power? Do well, and so shalt thou have praise of the same. 4 For he is the minister of God for thy wealth. But if thou do evil, fear: For he beareth not the sword for nought, for he is the minister of God, to take vengeance on him that doth evil. 5 Wherefore, ye must be subject, not because of wrath only, but also for conscience's sake. 6 For, for this cause ye pay also tribute: for they are Gods ministers, applying themselves for the same thing. 7 Give to all men therefore their duty: tribute, to whom ye owe tribute; custom, to whom custom; fear, to whom fear; honor, to whom ye owe honor. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1 Let every person be subject to the governing authorities., For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. 2 Therefore he who resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. 3 For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of him who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, 4 for he is God's servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain; he is the servant of God to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer. 5 Therefore one must be subject, not only to avoid God's wrath but also for the sake of conscience. 6 For the same reason you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, attending to this very thing. 7 Pay all of them their dues, taxes to whom taxes are due, revenue to whom revenue is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

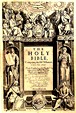

During Bloody Mary's reign English translations of the Bible were suppressed, and their use in churches was forbidden. The Geneva Bible was the work of English exiles who gathered in the Calvinist stronghold of Geneva under the direction of the divines Miles Coverdale and John Knox to revise Coverdale's "Great Bible" of 1539. Set in legible Roman type, divided on Calvin's advice into numbered verses, and easier to heft than its massive predecessors, it appeared in 1560, dedicated to Elizabeth, and became at once the household Bible of the land. Its staunchly Calvinist authors added instructive glosses on history, geography, and theology in its margins. These annotations, amounting to nearly 300,000 words, about a third as many as the Bible itself, were written by leading Reformation theologians including John Knox, Miles Coverdale, Theodore Beza, and John Calvin himself. Those to Romans 13 are telling. Of Paul they comment: "He distinctly shows what subjects owe to their magistrates, that is, obedience: from which he shows that no man is free: and the obedience we owe is such that it is not only due to the highest magistrate himself, but also even to the lowest, who has any office under him." Their conclusion reveals the political force that Scripture has; because no one is above civil authority, "Therefore the tyranny of the pope over all kingdoms must be thrown down to the ground." "Because God is author of this order," he stands behind the authority of all princes and rulers, "so that those who are rebels ought to know that they make war with God himself: and because of this they purchase for themselves great misery and calamity." Their reading of the passage is immersed in the political debate over the limits of monarchical authority, and the position they take is the position of the state and throne. "The conclusion" they draw is that "we must obey the magistrate, not only for fear of punishment, but much more because (although the magistrate has no power over the conscience of man, yet seeing he is God's minister) he cannot be resisted by any good conscience. So far as we lawfully may: for if unlawful things are commanded to us, we must answer as Peter teaches us, 'It is better to obey God than men.' Only the inner voice of conscience lies beyond the ruler's power (note that "ruler" has replaced "magistrate" in the King James Version). And conscience itself forbids that any subject rise up against his ruler. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During the Middle Ages political thinkers turned Paul's injunction to obey secular authority as the basis for the theory of the divine right of kings. The great thirteenth-century compendium of medieval law On the Laws and Customs of England (De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliae) ascribed to Henry Bracton, flatly asserts:

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Because God ordains kings, the theory goes, their right to their thrones is absolute. And just as God made Solomon king and established the house of David, a king must be succeeded by his first-born son or nearest heir. The right he acquires by birth cannot be forfeited. So long as an heir lives, he is king by hereditary right, no matter how long usurpers may have reigned. Kings, moreover, answer to God alone. They are above the law except in the fact that they cannot surrender, limit, or share the sovereignty that God has vested entirely in them. Their subjects are commanded to obey them by God Himself. Good or bad, kings are God's deputies on Earth, and to oppose their will is to oppose the will of God and thus to risk one's immortal soul. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Shakespeare's time, this idea had become formalized in the concept of the two bodies of the king, a legal fiction that separated the king's spiritual or legal existence as ruler from his physical body. The monarch, they thought, was composed of two bodies, a body natural and a body politic contained within the natural body of the monarch. His natural body was subject to the weaknesses of the flesh, but the body politic was held to be unerring and immortal. Although kings and subjects died, the realm endured: "the King is dead, long live the king." Writing in 1571, the lawyer Edmund Plowden described this view of the crown: |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These two bodies, the fallible individual and mortal body and the flawless, abstract and immortal body, are fused at the moment of coronation. Moreover, the king's divinity prevented any separation of the two bodies. As long as the monarch's natural body held out, the body politic remained vested in him. The doctrine also gave a mystical sanction to inheritance of the title. Just as God ordained His kings, He ordained His kings' successors. Primogeniture, the inheritance of the crown by the first-born son, was both a natural law and also a divine law.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE EMERGENCE OF RESISTANCE TO THE STATE St. Paul's injunction in the Bible that secular authority must be obeyed because it was divinely ordained would seem quite unequivocal.The Old Testament contains many instances of a wicked ruler chosen by God to punish a wicked people, so to rise up against even a wicked ruler would seem to oppose God's will. While subjects must obey their consciences and refuse to carry out any ungodly order, they must not actively resist their ruler's authority. When Martin Luther broke with the Pope, he denied that the Church had any power of coercion; such power to punish, he insisted, belonged only to secular rulers. Both he and Calvin accepted their temporal authority even when they rejected that of the pope. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But when powerful rulers like Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, tried to suppress the Reformation, Luther and later Calvin changed their minds. Surely, they argued, God did not mean for them to remain passive while the true religion, which He had chosen to reveal to them, was trampled down by unrighteous princes? If a king or prince tried to "exterminate the pure teaching of the Holy Gospel," Luther's ally Philipp Melanchthon wrote, "then the lower godfearing magistrate may defend himself and his subjects." The Old Testament offered examples of civil authorities resisting their rulers, preserving "the people of God from evil and defend[ing]their safety and goods. When superior power falls to extortion or causes any other kind of external injury," reformer Martin Bucer wrote, magistrates beneath him could "attempt to remove him by forces of arms." While Jean Calvin denied the right to resist a tyrant to commoners, or "private men," he insisted that "inferior" magistrates, who held offices under the monarch, were obliged to defend the people's interest when kings turned tyrant. For though the correcting of unbridled government bee the revengement of the Lord, let us not by and by thinke that it is committed to us, to whom there is given no other conmandement but to obey and suffer. I speake always of private men. For if there bee at this time ... Magistrates for the behalfe of the people . . . I doe not forbid them according to their office to withstand the outraging licentiousnesse of kings: that I affirme that if they winke at kings wilfully ranging over and treading downe the poore communalty, their dissembling is not without wicked breach of faith, because they decitfully betray the liberty of the people, whereof they know themselves to bee appointed protectors by the ordinance of God. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

English Protestants made the same arguments when Mary Tudor became queen and restored the Roman religion. In 1556 John Ponet, who had been Bishop of Rochester and Winchester until his opposition to Mary drove him into exile in Martin Bucer's Strasbourg, anonymously published A Short Treatise of Politic Power. There he asked "Whether it be lawful to depose an evil governor and kill a tyrant." "England lacketh not the practice and experience," he pointed out, "for they deprived King Edward the Second, because without law he killed his subjects, spoiled them of their goods, and wasted the treasure of the realm." And Richard II was "thrust out" for much the same "just cause." Kings and princes do not have an absolute power over their subjects, Ponet asserted. They are themselves subject both to the laws of God and men, and they can be punished for breaking those laws by the same civil authorities or magistrates who try and punish common people. Citing the familiar analogy between the body politic and the human body that Shakespeare later uses in Coriolanus (1.1.93-155), Ponet denied that deposing a monarch would destroy the state: "albeit they are the heads of a politic body," he wrote, "yet they are not the whole body. . . they are but members." |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

JOHN PONET, A SHORT TREATISE OF POLITIC POWER (1556)

Whether It Be Lawful To Depose An Evil Governor, And Kill A Tyrant

As there is no better nor happier commonwealth nor no greater blessing of God, than where one ruleth, if he be a good, just and godly man: so is there no worse nor none more miserable, nor greater plague of God than where one ruleth, that is evil, unjust and ungodly. . . . An evil person coming to the government of any state, either by usurpation, or by election or by succession, utterly neglecting the cause why kings, princes and other governors in commonwealths be made (that is, the wealth of the people) seeketh only or chiefly his own profit and pleasure. And as a sow coming into a fair garden, rooteth up all the fair and sweet flowers and wholesome simples [medicinal herbs], leaving nothing behind, but her own filthy dirt: so doth an evil governor subvert the laws and orders, or maketh them to be wrenched or racked to serve his affections, that they can no longer do their office. He spoileth the people of their goods, either by open violence, making his ministers to take it from them without payment therefore, or promising and never paying: or craftily under the name of loans, benevolences, contributions, and such like gay painted words, or for fear he getteth out of their possession that they have, and never restoreth it. . . . |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But as an hunter maketh wild beasts his prey, and useth toils, nets, snares, traps, dogs, ferrets, mining and digging the ground, guns, bows, spears, and all other instruments, engines, devises, subtleties, and means, whereby he may come by his prey: so doth a wicked governor make the people his game and prey, and useth all kinds of subtleties, deceits, crafts, policies, force, violence, cruelty and such like devilish ways, to spoil and destroy the people, that be committed to his charge. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now for as much as there is no express positive law for punishment of a Tyrant among Christian men, the question is, whether it be lawful to kill such a monster and cruel beast covered with the shape of a man. . . . England lacketh not the practice and experience of the same. For they deprived King Edward the second, because without law he killed his subjects, spoiled them of their goods, and wasted the treasure of the realm. And upon what just cause Richard the second was thrust out, and Henry the fourth put in his place, I refer it to their own judgment. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And seeing it is before manifestly and sufficiently proved, that kings and princes have not an absolute power over their subjects: that they are and ought to be subject to the law of God, and the wholesome positive laws of their country, and that they may not lawfully take or use their subjects' goods at their pleasure: the reasons, arguments and law that serve for the deposing and displacing of an evil governor, will do as much for the proof, that it is lawful to kill a tyrant, if they may be indifferently heard. As God hath ordained Magistrates to hear and determine private men's matters, and to punish their vices, so also will he, that the magistrates' doings be called to account and reckoning, and their vices corrected and punished by the body of the whole congregation or commonwealth. . . . For it is no private law to a few or certain people, but common to all: not written in books, but graffed in the hearts of men; not made by man, but ordained of God, which we have not learned, received or read, but have taken, sucked and drawn it out of nature, whereunto we are not taught, but made, not instructed, but seasoned, and (as S[aint] Paul saith) man's conscience bearing witness of it. |

"It is lawful |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This law testifieth to every man's conscience, that it is natural to cut away an incurable member, which (being suffered) would destroy the whole body. . . . Kings, Princes and other governors, albeit they are the heads of a politic body, yet they are not the whole body. And though they be the chief members, yet they are but members: neither are the people ordained for them, but they are ordained for the people. . . . |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But I beseech thee, what needeth to make one general law to punish by one name a great many offenses, when the law is already made for the punishment of every one of them particularly? If a prince rob and spoil his subjects, it is theft, and as a thief he ought to be punished. If he kill and murder them contrary or without the laws of his country, it is murder, and as a murderer he ought to be punished. If he commit adultery, he is an adulterer and ought to be punished with the same pains that others be. If he violently ravish men's wives, daughters, or maidens, the laws that are made against ravishers ought to be executed on him. If he go about to betray his country, and to bring the people under a foreign power, he is a traitor, and as a traitor he ought to suffer. . . . Fear no man, for ye execute the judgment of God, saith the holy ghost by the mouth of Moses. Judge not after the outward appearance of men, but judge rightly, saith Christ. |

"Kings are |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE PROTESTANT THEORY OF RESISTANCE The theory of resistance spread wherever the people's conscience resisted a ruler's attempt to impose her own faith upon them. In Scotland in 1558, when the marriage of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, to the Catholic heir to the throne of France threatened the newly reformed Scottish church, a Scots Calvinist named Christopher Goodman, co-pastor to John Knox and one of the authors of the Geneva translation of the Bible, affirmed in a broadside entitled How Superior Powers ought to be obeyed of their subjects; and wherein they may lawfully by God's word be disobeyed and resisted: |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When kings or rulers become blasphemers of God, oppressors and murderers of their subjects, they ought no more to be accounted kings or lawful magistrates, but as private men to be examined, accused, condemned and punished by the law of God, and being condemned and punished by that law, it is not man's but God's doing . . . When magistrates cease to do their duty, the people are as it were without magistrates . . . If princes do right and keep promise with you, then do you owe them all humble obedience. If not, ye are discharged and your study ought to be in this case how ye may depose and punish according to the law such rebels against God and oppressors of their country. |

"Depose and punish |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1562, the bloody Wars of Religion broke out between the French Calvinists, the Huguenots, and Catholic forces led by the Guise family. When the young French king fell under the sway of the Huguenots, his mother, , fearing the loss of her own influence, enticed her son into a plot she had hatched with Catholic nobles to exterminate the Huguenot leaders, then in Paris for the wedding of Catherine's daughter to the Huguenot King of Navarre. On August 24, 1572, the eve of the feast day of St. Bartholomew, they massacred 3,000 Huguenots. The homes and shops of Huguenots were pillaged, and their occupants brutally murdered; many bodies were thrown into the Seine. The bloodshed spread to the provinces, and as many as 70,000 Huguenots may have be slain. A gleeful Pope Gregory XIII celebrated the massacre by having a commendatory medal struck. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Huguenots, like the English under Bloody Mary, repudiated Calvin's belief, grounded in Scripture, that civil authorities, ordained by God, must always be obeyed. Instead they developed the theory that rulers who broke God's laws were tyrants who must be made to answer to the laws of God and of the state. In 1579 a pseudonymous pamphlett first attributed to Philippe Duplessis-Mornay, a Huguenot who had barely escaped death himself on St. Bartholomew's Eve, proclaimed the right of subjects to overthrow their rulers in Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos. Other scholars attribute the tract to the humanist Hubert Languet, who was an intimate of Sir Philip Sidney, poet, soldier, and protege of two of Elizabeth's most powerful ministers. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Writing under the name of Junius Brutus, founder of the Roman Republic, the author argued that nations, like all communities, originated in covenants between the ruler and his people like the covenant between each of them and God. In a just and godly community, the people's first allegiance was to God, not their secular lord, who was merely God's deputy. If the ruler broke faith with God and violated his covenant with the people, he forfeited his right to rule and his subjects must resist him. Kings, he insisted, were not above the law, and magistrates, whose duty was to enforce the law, were obligated to enforce it even when the lawbreaker was the king. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

PHILIPPE DUPLESSIS-MORNAY, VINDICIAE CONTRA TYRANNOS (1579) The First Question: Whether Subjects Are Bound and Ought to Obey Princes, if They Command That Which is Against the law of God? This question . . . seems to make a doubt of an axiom always held infallible amongst Christians, confirmed by many testimonies in Holy Scripture, divers examples of the histories of all ages, and by the death of all the holy martyrs. For it may well be demanded wherefore Christians have endured so many afflictions, but that they were always persuaded that God must be obeyed simply and absolutely, and kings with this exception, that they command not that which is repugnant to the law of God. Otherways wherefore should the apostles have answered that God must rather be obeyed then men? And also seeing that the only will of God is always just, and that of men may be, and is, oftentimes unjust, who can doubt but that we must always obey God's commandments without any exception, and men's ever with limitation? . . . |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are many princes in these days calling themselves Christians which arrogantly assume an unlimited power over which God himself hath no command, and . . . they have no want of flatterers which adore them as gods upon earth . . . The princes exceed their bounds, not contenting themselves with that authority which the almighty and all good God hath given them, but seek to usurp that sovereignty which He hath reserved to Himself over all men, being not content to command the bodies and goods of their subjects at their pleasure, but assume license to themselves to enforce the consciences, which appertains chiefly to Jesus Christ. Holding the earth not great enough for their ambition, they will climb and conquer heaven itself. The people, on the other side . . . instead of resisting them, if they have means and occasion, suffer them to usurp the place of God, making no conscience to give that to Caesar which belongs properly and only to God. . . . |

"They will climb |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It then belongs to princes to know how far they may extend their authority, and to subjects in what they may obey them, if subjects be bound to obey kings in case they command that which is against the law of God: that is to say, to which of the two (God or king) must we rather obey? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First, the Holy Scripture doth teach that God reigns by His own proper authority, and kings by derivation; God from Himself, kings from God; that God hath a jurisdiction proper, kings are His delegates. It follows then that the jurisdiction of God hath no limits, that of kings is bounded; that the power of God is infinite, that of kings confined; that the kingdom of God extends itself to all places, that of kings is restrained within the confines of certain countries. In like manner God hath created of nothing both heaven and earth, wherefore by good right He is lord and true proprietor . . . and all men, of what degree or quality soever they be, are His servants, farmers, officers, and vassals, and owe account and acknowledgment to Him. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

God does not at any time divest Himself of His power. He holds a scepter in one hand to repress and quell the audacious boldness of those princes who mutiny against Him, and in the other a balance to control those who administer not justice with equity as they ought. . . . Therefore all kings are the vassals of the King of Kings, invested into their office by the sword, which is the cognizance of their royal authority, to the end that with the sword they maintain the law of God, defend the good, and punish the evil. . . . |

"All kings are |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now if we consider what is the duty of vassals, we shall find that what may be said of them agrees properly to kings. . . . The vassal receives laws and conditions from his sovereign. God commands the king to observe his laws and to have them always before his eyes, promising that he and his successors shall possess long the kingdom if they be obedient, and, on the contrary, that their reign shall be of small continuance if they prove rebellious to their sovereign king. . . . The vassal loses his fee [fief] if he commit a felony, and by law forfeits all his privileges. In the like case the king loses his right, and many times his realm also, if he despise God, if he complot with His enemies, and if he commit felony against that royal majesty. This will appear more clearly by the consideration of the covenant which is contracted between God and the king, for God does that honor to His servants to call them His confederates. Now we read of two sorts of covenants at the inaugurating of kings: the first between God, the king, and the people, that the people might be the people of God; the second between the king and the people, that the people shall obey faithfully and the king command justly. . . . If a prince usurps the right of God, and puts himself forward, after the manner of the giants, to scale the heavens, he is no less guilty of high treason to his sovereign, and commits felony in the same manner as if one of his vassals should seize on the rights of his crown, and puts himself into evident danger to be despoiled of his estates; and that so much the more justly, there being no proportion between God and an earthly king, between the Almighty and a mortal man, whereas yet between the lord and the vassal there is some relation of proportion. . . . kings are the vassals of God and deserve to be deprived of the benefit they receive from their lord if they commit felony, in the same fashion as rebellious vassals are of their estates. These premises being allowed, this question may be easily resolved; for if God hold the place of sovereign lord, and the king as vassal, who dare deny but that we must rather obey the sovereign than the vassal? If God commands one thing and the king commands the contrary, what is that proud man that would term him a rebel who refuses to obey the king, when else he must disobey God? |

"We must |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Second Question: Whether It Be Lawful to Resist a Prince Who Doth Infringe the Law of God or Ruin His Church? By Whom, How, and How Far Is It Lawful? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But I see well, here will be an objection made. What will you say? That a whole people, that beast of many heads, must they run in a mutinous disorder to order the business of the commonwealth? What address or direction is there in an unruly and unbridled multitude? What counsel or wisdom to manage the affairs of state? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When we speak of all the people we understand by that only those who hold their authority from the people: to wit, the magistrates, who are inferior to the king, and whom the people have substituted or established, as it were, consorts in the empire and with a kind of tribunitial authority to restrain the encroachments of sovereignty and to represent the whole body of the people. as it is lawful for a whole people to resist and oppose tyranny, so likewise the principal persons of the kingdom may, as heads and for the good of the whole body, confederate and associate themselves together. And as in a public state that which is done by the greatest part is esteemed and taken as the act of all, so in like manner must it be said to be done which the better part of the most principal have acted-briefly, that all the people had their hand in it. |

"It is lawful for a |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Briefly, for so much as none were ever born with crowns on their heads and scepters in their hands, and that no man can be a king by himself, no reign without people“whereas, on the contrary, the people may subsist of themselves, and were long before they had any kings“it must of necessity follow that kings were at the first constituted by the people. And although the sons and dependents of such kings, inheriting their fathers' virtues, may in a sort seem to have rendered their kingdoms hereditary to their offsprings, and that in some kingdoms and countries the right of free election seems in a sort buried, yet notwithstanding, in all well-ordered kingdoms this custom is yet remaining. The sons do not succeed the fathers before the people have first, as it were, anew established them by their new approbation. Neither were they acknowledged in quality as inheriting it from the dead, but approved and accounted kings then only when they were invested with the kingdom by receiving the scepter and diadem from the hands of those who represent the majesty of the people. |

"None were ever |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If it be objected that kings were enthronised and received their authority from the people who lived five hundred years ago, and not by those now living, I answer that the commonwealth never dies, although kings be taken out of this life one after another. For as the continual running of the water gives the river a perpetual being, so the alternative revolution of birth and death renders the people immortal. The only duty of kings and emperors is to provide for the people' good. The kingly dignity, to speak properly, is not a tide of honor but a weighty and burdensome office. It is not a discharge or vacation from affairs to run a licentious course of liberty, but a charge and vocation to all industrious employments for the service of the commonwealth. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When therefore that these words of mine and thine entered into the world, and that differences fell amongst fellow citizens touching the propriety of goods, and wars amongst neighboring people about the right of their confines, the people bethought themselves to have recourse to someone who both could and should take order that the poor were not oppressed by the rich, nor the patriots wronged by strangers. . . . Seeing then that kings are ordained by God and established by the people to procure and provide for the good of those who are committed unto them, and that this good or profit be principally expressed in two things, to wit, in the administration of justice to their subjects and in the managing of armies for the repulsing their enemies“certainly we must infer and conclude from this that the prince who applied himself to nothing but his peculiar profits and pleasures, or to those ends which most readily conduce thereunto; who contemns and perverts all laws; who uses his subjects more cruelly than the barbarous enemy would do: he may truly and really be called a tyrant and those who in this manner govern their kingdoms, be they of never so large an extent, are more properly unjust pillagers and freebooters than lawful governors. |

"Kings are |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE IDEOLOGY OF OBEDIENCE

Ironically, when Protestants like James and Elizabeth ascended the throne, they found that the same arguments against tyranny could be applied to them. In the wake of the Northern Rising, inspired in part by Catholics struggling to restore their true faith and in part by nobles out of favor with Elizabeth and her councillors, and especially after her excommunication by the Pope |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The papal bull that excommunicated heretical monarchs, Regnans in Excelsis (1570), denied Elizabeth her divine right, God's sanction of her power.

|

Their response was "An Homily against Disobedience and Wilfull Rebellion," hurredly added to the Homilies in 1570 after Elizabeth's excommunication. The Homilies were sermons composed to be read in all churches on Sundays and holy days. Twelve homilies, most written by Thomas Cranmer, had appeared in 1547, after the death of Henry VIII and a second series, in 1562. Since all subjects were members of the established church and required by law to attend services, every man, woman, and child in England should at least have heard the homilies several times a year for life.

The Church of England, with the monarch at its head, was an ideological apparatus of the state, which used it to disseminate its justification of monarchy, and the "Homily against Disobedience" is explicitly a political document. The last and longest of the Homilies, it was framed to forestall rebellions by Elizabeth's Catholic subjects, freed by the Pope from obedience to a heretical and excommunicated sovereign.

The "Homilie" makes the government's case against insurrection by justifying all monarchy, deriving the monarch's absolute rule from God's primal commandment of obedience. "Obedience," its authors assert, is "the very root of all virtues, and the cause of all felicity." It is the basis of man's unfallen condition; all sorrow and suffering are consequences of man's first disobedience.

|

|

God ordains all human law and authority to repair the fall of man and restore the rule of obedience:lest all things should come unto confusion and utter ruin, God forthwith by laws given unto mankind, repaired again the rule and order of obedience thus by rebellion overthrown, and besides the obedience due unto his Majesty, he not only ordained that in families and households, the wife should bee obedient unto her husband, the children unto their parents, the servants unto their masters: but also, when mankind increased, and spread itself more largely over the world, he by his holy word did constitute and ordain in cities and countries several and special governors and rulers, unto whom the residue of his people should be obedient.

|

|

Monarchy mediates between God's rule over all Creation and the patriarch's rule over family and household. Like family and class, the origins of the state are divine. Obedience to the monarch, then, is but another step in hierarchical patriarchy: the hierarchies of class and gender derive from the same divine ordinance.

|

|

Because God confers His legitimacy on all monarchs, so all monarchs must be obeyed. Scripture teaches that "Kings and Princes, as well the evil as the good, do reign by Gods ordinance," and "God defendeth them against their enemies, and destroyeth their enemies horribly." To disobey a monarch is to offend God: "the subject that provoketh him to displeasure, sinneth against his own soul." Obedience speaks with an inner voice to the elect: "ye must be subject, not because of wrath only but also for conscience sake."

|

This next move is crucial, because it gives voice to the radical argument that chance or their own ambition crowns princes, the very argument that the "Homilie" exists to refute. Only here do we hear the unspoken or silenced voices that contest and threaten to subvert monarchy:

|

|

|

|

God Himself ordains sovereignty and chooses his sovereigns. He grants some men and women dominion over their fellows just as He grants Adam dominion over the animals. And just as He ordains the institution of rule, He selects each ruler. Dominion, one man's power over another, is not a consequence of human iniquity, a lust for power in the breast of the fallen, but its repair. And no prince achieves his power by the random or fickle promptings of fortune; neither the institution nor the person who occupies it is contingent.

|

|

God is himself a monarch, and earthly monarchs should emulate "his heavenly governance, as the majesty of heavenly things may by the baseness of earthly things be shadowed and resembled." The good prince expresses God's mercy; the bad expresses His wrath and justice. To rebel against a bad king is to leave it to his subjects to judge him, "as though the foot must judge of the head." Rebellion "is the greatest of all mischiefs," and "a rebel is worse than the worse prince."

|

Thus, to rebel against a bad king is to disobey God twice: by provoking Him to give his subjects a bad king in the first place and then by revolting against that king, and thus against God's judgment upon his subjects, in the second: "God places as well evil Princes as good."

|

|

"A THE FIRST PART As God the Creator and Lord of all things appointed his Angels and heavenly creatures in all obedience to serve and to honor his majesty: so was it his will that man, his chief creature upon the earth, should live under the obedience of his Creator and Lord: and for that cause, God, as soon as he had created man, gave unto him a certain precept and law, which he (being yet in the state of innocency, and remaining in Paradise) should observe as a pledge and token of his due and bounden obedience, with denunciation of death if he did transgress and break the said law and commandment. And as God would have man to be his obedient subject, so did he make all earthly creatures subject unto man, who kept their due obedience unto man, so long as man remained in his obedience unto God: in the which obedience if man had continued still, there had been no poverty, no diseases, no sickness, no death, nor other miseries wherewith mankind is now infinitely and most miserably afflicted and oppressed. So here appeareth the original kingdom of God over Angels and man, and universally over all things, and of man over earthly creatures which God had made subject unto him, and with all the felicity and blessed state, which Angels, man, and all creatures had remained in, had they continued in due obedience unto God their King. For as long as in this first kingdom the subjects continued in due obedience to God their king, so long did God embrace all his subjects with his love, favor, and grace, which to enjoy, is perfect felicity, whereby it is evident, that obedience is the principal virtue of all virtues, and indeed the very root of all virtues, and the cause of all felicity. But as all felicity and blessedness should have continued with the continuance of obedience, so with the breach of obedience, and breaking in of rebellion, at vices and miseries did withal break in, and overwhelm the world. The first author of which rebellion, the root of all vices, and mother of all mischiefs, was Lucifer, first God's most excellent creature, and most bounden subject, who by rebelling against the Majesty of God, of the brightest and most glorious Angel, is become the blackest and most foulest fiend and devil: and from the height of heaven, is fallen into the pit and bottom of hell.

|

. . . Thus became rebellion, as you see, both the first and the greatest, and the very first of all other sins, and the first and principal cause, both of all worldly and bodily miseries, sorrows, diseases, sicknesses, and deaths, and which is infinitely worse then all these, as is said, the very cause of death and damnation eternal also. After this breach of obedience to God, and rebellion against his Majesty, all mischiefs and miseries breaking in therewith, and overflowing the world, lest all things should come unto confusion and utter ruin, God forthwith by laws given unto mankind, repaired again the rule and order of obedience thus by rebellion overthrown, and besides the obedience due unto his Majesty, he not only ordained that in families and households, the wife should be obedient unto her husband, the children unto their parents, the servants unto their masters: but also, when mankind increased, and spread itself more largely over the world, bee by his holy word did constitute and ordain in Cities and Countries several and special governors and rulers, unto whom the residue of his people should be obedient. "His holy word

|

As in reading of the Holy Scriptures, we shall find . . . that Kings and Princes, as well the evil as the good, do reign by God's ordinance, and that subjects are bounden to obey them: that God doth give Princes wisdom, great power, and authority: that God defendeth them against their enemies, and destroyeth their enemies horribly: that the anger and displeasure of the Prince, is as the roaring of a lion, and the very messenger of death: and that the subject that provoketh him to displeasure, sinneth against his own soul: . . . Kings, Queens, and other Princes (for he speaketh of authority and power, be it in men or women) are ordained of God, are to be obeyed and honored of their subjects: that such subjects, as are disobedient or rebellious against their Princes, disobey God, and procure their own damnation: that the government of Princes is a great blessing of God, given for the common wealth, specially of the good and godly: for the comfort and cherishing of whom God giveth and setteth by princes: and on the contrary part, to the fear and for the punishment of the evil and wicked. "Subjects rebellious

|

. . . It cometh therefore neither of chance and fortune (as they term it) nor of the ambition of mortal men and women climbing up of their own accord to dominion, that there bee Kings, Queens, Princes, and other governors over men being their subjects: but all Kings, Queens, and other governors are specially appointed by the ordinance of God. . . . so hath he constituted, ordained and set earthly Princes over particular Kingdoms and Dominions in earth, both for the avoiding of all confusion, which else would be in the world, if it should be without governors, and for the great quiet and benefit of earthly men their subjects. "Neither of chance What shall subjects do then? shall they obey valiant, stout, wise, and good princes, and contemn, disobey, and rebel against children being their princes, or against undiscreet and evil governors? God forbid: for first what a perilous thing were it to commit unto the subjects the judgment which prince is wise and godly, and his government good, and which is otherwise: as though the foot must judge of the head: an enterprise very heinous, and must needs breed rebellion. For who else be they that are most inclined to rebellion, but such haughty spirits? from whom springeth such foul ruin of Realms? Is not rebellion the greatest of all mischiefs? And who are most ready to the greatest mischiefs, but the worst men? . . . a rebel is worse than the worst prince, and rebellion worse than the worst government of the worst prince that hitherto hath been: both rebels are unmeet ministers, and rebellion an unfit and unwholesome medicine to reform any small lacks in a prince, or to cure any little griefs in government . . . Shall the subjects both by their wickedness provoke God for their deserved punishment, to give them an undiscreet or evil prince, and also rebel against him, and withal against God, who for the punishment of their sins did give them such a prince? Will you hear the Scriptures concerning this point? God (say the holy Scriptures)' maketh a wicked man to reign for the sins of the people. Again, God giveth a prince in his anger, meaning an evil one, and taketh away a prince in his displeasure, meaning specially when he taketh away a good prince for the sins of the people. . . . Here you see, that God placeth as well evil Princes as good. "A rebel is

|

THE ABSOLUTIST STATE

"An Homily against Disobedience" advances the argument that Shakespeare's John of Gaunt, England's prophetic voice, does in Richard II:

|

|

At the same time that Elizabeth's Protestant government found it useful to invoke St. Paul's notion of the monarch's divine right, a new argument in favor of obedience to the monarch's absolute authority was emerging from a new centrist party in France. Made up of Catholics and Protestants and headed by the Duke of Alençon, the Politiques recoiled from the devastation and disorder wreaked upon the nation by the Wars of Religion. The only way to reestablish the rule of law, they felt, was to unite around a powerful monarch, whose authority was absolute. The argument found brilliant expression in 1576 in Jean Bodin's Six Books of a Commonweal.

|

Bodin's intervention was to define sovereignty as an "absolute and perpetual power" vested in the monarch. It derived not from a covenant with the people but from God alone. The monarch answered only to God, not the people. Laws were only an expression of the monarch's will, and they were binding on him only as long as he chose to follow them. Since the monarch's sovereignty came directly from God, his subjects could not rightfully oppose his will. Their duty, in the face of his absolute power, was complete obedience.

|

JEAN BODIN, THE SIX BOOKS OF A COMMONWEAL (1576) OF SOVEREIGNTY Majesty or sovereignty is the most high, absolute, and perpetual power over the citizens and subjects in a commonweal. . . . So here it behoveth first to define what majesty or sovereignty is, which neither lawyer nor political philosopher hath yet defined, although it be the principal and most necessary point for the understanding of the nature of a commonweal. And forasmuch as we have before defined a commonweal to be the right government of many families, and of things common amongst them, with a most high and perpetual power, it resteth to be declared what is to be understood by the names of a most high and perpetual power. "The most high,

|

We have said that this power ought to be perpetual, for that it may be that at that absolute power over the subjects may be given to one or many, for a short or certain time; which expired, they are no more than subjects themselves. So that whilst they are in their puissant authority, they cannot call themselves sovereign princes, seeing that they are but men put in trust, and keepers of this sovereign power, until it shall please the people or the prince that gave it them to recall it, who always remained seized [in possession] thereof. For as they which lend or pawn unto another man their goods remain still the lords and owners thereof, so it is also with them who give unto others power and authority to judge and command, be it for a certain time limited or so great and long time as shall please them“they themselves nevertheless continuing still seized of the power and jurisdiction, which the other exercise but by way of loan or borrowing....

|

|

But let us grant an absolute power, without appeal or controlment, to be granted by the people to one or many, to manage their estate and entire government. Shall we therefore say him or them to have the state of sovereignty, whenas he only is to be called absolute sovereign who next unto God acknowledgeth none greater than himself? Wherefore I say no sovereignty to be in them, but in the people, of whom they have a borrowed power, or power for a certain time; which once expired, they are bound to yield up their authority. Neither is the people to be thought to have deprived itself of the power thereof, although it have given an absolute power to one or more for a certain time: and much more if the power (be it given) be revocable at the pleasure of the people, without any limitation of time. For both the one and the other hold nothing of themselves, but are to give account of their doings unto the prince or the people of whom they had the power to command. Whereas the prince or people themselves, in whom the sovereignty resteth, are to give account unto none but to the immortal God alone. . . . "To give account

|

Now let us prosecute the other part of our propounded definition, and show what these words absolute power signify. For we said that unto majesty, or sovereignty, belongeth an absolute power not subject to any law. For the people or the lords of a commonweal may purely and simply give the sovereign and perpetual power to anyone, to dispose of the goods and lives and of all the state at his pleasure, and so afterward to leave it to whom he list; like as the proprietor or owner may purely and simply give his own goods, without any other cause to be expressed than of his own mere bounty“which is indeed the true donation, which no more receiveth condition, being once accomplished and perfected. As for the other donations, which carry with them charge and conditions, [they] are not indeed true donations. So also the chief power, given unto a prince with charge and condition, is not properly sovereignty, nor power absolute except that such charge or condition annexed unto the sovereignty at the creation of a prince be directly comprehended within the laws of God and nature. . . . "Unto majesty

|

If we shall say that he only hath absolute power which is subject unto no law, there should then be no sovereign prince in the world, seeing that all princes of the earth are subject unto the laws of God, of nature, and of nations. . . . But it behoveth him that is a sovereign not to be in any sort subject to the command of another. . . . [His] office it is to give laws unto his subjects, to abrogate laws unprofitable, and in their stead to establish other; which he cannot do that is himself subject unto laws, or to others which have command over him. And that is it for which the law saith that the prince is acquitted from the power of the laws. And this word, the law, in the Latin importeth the commandment of him which hath the sovereignty. . . . If then the sovereign prince be exempted from the laws of his predecessors, much less should he be bound unto the laws and ordinances he maketh himself. For a man may well receive a law from another man, but impossible it is in nature for to give a law unto himself, no more than it is to command a man's self in a matter depending of his own will. . . . And as the pope can never bind his own hands (as the canonists say), so neither can a sovereign prince bind his own hands, albeit that he would. We see also in the end of all edicts and laws these words, Quia sic nobis placuit, "Because it hath so pleased us"; to give us to understand that the laws of a sovereign prince, although they be grounded upon good and lively reasons, depend nevertheless upon nothing but his mere and frank goodwill. "The laws of a

|

But as for the laws of God and nature, all princes and people of the world are unto them subject. Neither is it in their power to impugn them, if [they] will not be guilty of high treason to the divine majesty, making war against God, under the greatness of whom all monarchs of the world ought to bear the yoke and to bow their heads in all fear and reverence. Wherefore, in that we said the sovereign power in a commonweal to be free from all laws, [that] concerneth nothing the laws of God and nature. "The sovereign

|

WHETHER IT BE LAWFUL TO LAY VIOLENT HAND UPON A TYRANT If the prince be an absolute sovereign . . . it is not lawful for any one of the subjects in particular, or all of them in general, to attempt anything, either by way of fact [i.e., deed] or of justice against the honor, life, or dignity of the sovereign, albeit that he had committed all the wickedness, impiety, and cruelty that could be spoken. For as to proceed against him by way of justice, the subject hath no such jurisdiction over his sovereign prince, of whom dependeth all power and authority to command. . . . Now if it be not lawful for the subject by way of justice to proceed against his prince . . . how should it then be lawful to proceed against him by way of fact or force? For question is not here of what men are able to do by strength and force, but what they ought of right to do: as not whether the subjects have power and strength, but whether they have lawful power to condemn their sovereign prince. Now the subject is not only guilty of treason in the highest degree who hath slain his sovereign prince, but even he also which hath attempted the same; who had given counsel or consent thereunto; yea, if he have concealed the same, or but so much as thought it. . . "It be not lawful

|

I cannot use a better example than of the duty of a son towards his father. The law of God saith that he which speaketh evil of his father or mother shall be put to death. Now if the father shall be a thief, a murderer, a traitor to his country . . . or what so you will else, I confess that all the punishments that can be devised are not sufficient to punish him. Yet I say that it is not for the son to put his hand thereunto. . . . Wherefore the prince, whom you may justly call the father of the country, ought to be unto every man dearer and more reverend than any father, as one ordained and sent unto us by God. I say, therefore, that the subject is never to be suffered to attempt anything against his sovereign prince, how naughty and cruel soever he be. Lawful it is, not to obey him in things contrary unto the laws of God and nature; to fly and hide ourselves from him; but yet to suffer stripes, yea, and death also, rather than to attempt anything against his life or honor. "The prince ought THE DIVINE RIGHT OF KING JAMES

Of all of England's rulers, however, the one most taken with Bodin's theory of absolute monarchy was James I. The great-grandson of the first Tudor king, Henry VII, James was a Tudor on his mother's side; she was Mary, Queen of Scots. James's father, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, descended from the same Tudor grandmother as Mary. When Darnley was murdered and Mary promptly married the leading suspect, an angry nation forced her into exile in England. In 1567, James, then not yet two years old, gained a throne but lost a mother. He was the sixth King James of Scotland.

|

|

But those who openly exercise their power, not for their country, but for themselves, and pay no regard to the public interest, but to their own gratification; who reckon the weakness of their fellow-citizens the establishment of their own authority, and who imagine royalty to be, not a charge entrusted to them by God, but a prey offered to their rapacity, are not connected with us by any civil or human tie, but ought to be put under an interdict, as open enemies to God and man.

|

Buchanan dedicated his treatise of elegant dialogues to the young King James VI of Scotland. Rarely has a teacher influenced his pupil less. Buchanan's insistence that kings were servants of their people fell on deaf ears. To James kings were gods on earth, invested with their powers by God and answerable only to God. For on his throne his scepter do they sway: And as their subjects ought them to obey So Kings should fear and serve their God again.

|

James expounded his claims of divine right in The True Law of Free Monarchies, published in 1598. In 1586 he had concluded a treaty with Elizabeth in which she acknowledged his right to succeed to the English throne, and the English no doubt read the absolutist claims in James's tract with some anxiety. While Elizabeth's government cited the same arguments and precedents against rebellion, she had never claimed the absolute authority of divine right. But James insisted that the king owns his realm as a vassal own his fief and might impose new laws by Royal Prerogrative, the unquestioned authority of the king.

|

KING JAMES VI, THE TRUE LAW OF FREE MONARCHIES, OR THE RECIPROCK AND MUTUAL DUTY BETWIXT A FREE KING AND HIS NATURAL SUBJECTS (1598) Shortly, then, to take up in two or three sentences, grounded upon all these arguments out of the law of God, the duty and allegiance of the people to their lawful king: their obedience, I say, ought to be to him as to God's lieutenant in earth, obeying his commands in all thing (except directly against God) as the commands of God's minister, acknowledging him a judge set by God over them, having power to judge them but to be judged only by God, whom-to only he must give account of his judgment; fearing him as their judge, loving him as their father, praying for him as their protector, for his continuance if he be good; for his amendment if he be wicked; following and obeying his lawful commands; eschewing and flying his fury in his unlawful, without resistance, but by sobs and tears to God, according to that sentence used in the primitive Church in the time of the persecution: Preces et lacrymae sunt arma ecclesiae ["Prayers and tears are the weapons of the Church"]. . . "Their lawful king

|

It is casten up by divers that employ their pens upon apologies for rebellions and treasons, that every man is born to carry such a natural zeal and duty to his commonwealth, as to his mother, that seeing it so rent and deadly wounded as whiles it will be by wicked and tyrannous kings, good citizens will be forced, for the natural zeal and duty they owe to their own native country, to put their hand to work for freeing their commonwealth from such a pest.

|

Whereunto I give two answers: First, it is a sure axiom in theology, that evil should not be done that good may come of it. The wickedness, therefore, of a king can never make them that are ordained to be judged by him, to become his judges. And if it not lawful to a private man to revenge his private injury upon his private adversary (since God hath only given the sword to the magistrate), how much less is it lawful to the people, or any part of them (who all are but private men; the authority being always with the magistrate, as I have already proved), to take upon them the use of the sword whom-to it belongs not, against the public magistrate, whom-to only it belongeth.

|

Next, in place of relieving the commonwealth out of distress (which is their only excuse and color) they shall heap double distress and desolation upon it, and so their rebellion shall procure the contrary effects that they pretend it for. For a king cannot be imagined to be so unruly and tyrannous but the commonwealth will be kept in better order, notwithstanding thereof by him than it can be by his way-taking. For first, all sudden mutations are perilous in commonwealths, hope being thereby given to all bare men to set up themselves and fly with other men's feathers, the reins being loosed, to all the insolencies that disordered people can commit by hope of impunity because of the looseness of all things. . . .

|

The second objection they ground upon the curse that hangs over the commonwealth where a wicked king reigneth. And, say they, there cannot be a more acceptable deed in the sight of God, nor more dutiful to their commonweal, than to free the country of such a curse, and vindicate to them their liberty, which is natural to all creatures to crave.

|

|

Whereunto, for answer, I grant indeed that a wicked king is sent by God for a curse to his people and a plague for their sins. But that it is lawful for them to shake off that curse at their own hand which God hath laid on them, that I deny, and may do so justly. . . . Patience, earnest prayers to God, and amendment of their lives, are the only lawful means to move God to relieve them of that heavy curse. As for vindicating to themselves their own liberty, what lawful Power have they to revoke to themselves again those privileges which their own consent before, were so fully put out of their hands? For if a prince cannot justly bring back again to himself the privileges once bestowed by him or his predecessors upon any state or rank of his subjects; much may the subjects maw [i.e., rob] out of the prince's hand that superiority which and his predecessors have so long brooked over them. "A wicked king

|

The last objection is grounded upon the mutual paction and adstipulation (as they call it) betwixt the king and his people at the time of his coronation. For there, they say, there is a mutual paction and contract bound up and sworn betwixt the king and the people. . . . I confess that a king at his coronation, or at the entry to his kingdom, willingly promises to his people to discharge honorably the truly the office given him by God over them. . . . Now in this contract (I say) betwixt the king and his people, God is doubtless the only judge, both because to him only the king must make count of his administration (as is oft said before), as likewise, by the oath in the coronation God is made judge and revenger of the breakers. For in his presence, as only judge of oaths, all oaths ought to be made.

|

Then since God is the only judge betwixt the two parties contractors, the cognition and revenge must only appertain to him. It follows therefore of necessity that God must first give sentence upon the king that breaks, before the people can think themselves free of their oath. What justice then is it that the party shall be both judge and party, usurping upon himself the office of God, may by this argument easily appear. And shall it then lie in the hands of [the] headless multitude, when they please to weary of subjection, to cast off the yoke of government that God has laid upon them, to judge and punish him, whom-by they should be judged and punished, and in that case wherein by their violence they kythe ["declare"] themselves to be most passionate parties to use the office of an ungracious judge or arbiter?

|

And therefore, since it is certain that a king, in case so it should fall out that his people in one body had rebelled against him, he should not in that case, as thinking himself free of his promise and oath, become an utter enemy and practice the wreck of his whole people and native country (although he ought justly to punish the principal authors and bellows of that universal rebellion), how much less then ought the people (that are always subject unto him and naked of all authority on their part) press to judge and overthrow him? . . . "The people are

|

And it is here likewise to be noted that the duty and allegiance which the people swears to their prince is not only bound to themselves, but likewise to their lawful heirs and posterity, the lineal succession of crowns being begun among the people of God and happily continued in divers Christian commonwealths. So as no objection either of heresy, or whatsoever private statute or law may free the people from their oath-giving to their king and his succession [as] established by the old fundamental laws of the kingdom.

|

For, as he is their heritable overlord, and so by birth, not by any right in the coronation, comes to his crown, it is alike unlawful (the crown ever standing full) to displace him that succeeds thereto as to eject the former. For at the very moment of the expiring of the king reigning the nearest and lawful heir enters in his place. And so to refuse him, or intrude another, is not to hold out one coming in, but to expel and put out their righteous king. "No objection may

|

When he first addressed Parliament in 1604, James echoed the resisters' creed. The king who exercises his power for his own gain is not a true king but a tyrant.

|

|

I do acknowledge, that the special and greatest point of difference that is between a rightful king and an usurping tyrant is in this: That whereas the proud and ambitious tyrant does think his kingdom and people are only ordained for satisfaction of his desires and unreasonable appetites; the righteous and just king does by the contrary acknowledge himself to be ordained for the procuring of the wealth and prosperity of his people, and that his greatest and principal worldly felicity must consist in their prosperity. If you be rich I cannot be poor: if you be happy I cannot but be fortunate: and I protest that your welfare shall ever be my greatest care and contentment: and that I am a servant it is most true, that as I am Head and Governor of all the people in my Dominion who are my natural vassals and subjects, considering them in numbers and distinct ranks; So if we will take the whole people as one body and mass, then as the head is ordained for the body, and not the body for the head; so must a righteous king know himself to be ordained for his people, and not his people for him. "A righteous king

|

Not that by all this former discourse of mine, and apology for kings, I mean that whatsoever errors and intolerable abominations a sovereign prince commit, he ought to escape all punishment, as if thereby the world were only ordained for kings, and they without controlment to turn it upside down at their pleasure. But by the contrary, by remitting them to God (who is their only ordinary judge) I remit them to the sorest and sharpest schoolmaster that can be devised for them, for the further a king is preferred by God above all other ranks and degrees of men, and the higher that his seat is above theirs, the greater is his obligation to his maker. And therefore in case he forget himself (his unthankfulness being in the same measure of height) the sadder and sharper will his correction be; and according to the greatness of the height he is in, the weight of his fall will recompense the same. For the further that any person is obliged to God, his offence becomes and grows so much the greater than it would be in any other. Jove's thunderclaps light oftener and sorer upon the high and stately oaks than on the low and supple willow trees, and the highest bench is slipperiest to sit upon. Neither is it ever heard that any king forgets himself towards God, or in his vocation, but God with the greatness of the plague revenges the greatness of his ingratitude. Neither think I by the force and argument of this my discourse so to persuade the people, that none will hereafter be raised up and rebel against wicked princes. But remitting to the justice and providence of God to stir up such scourges as pleases for punishment of wicked kings (who made the very vermin and filthy dust of the earth to bridle the insolency of proud Pharaoh), my only purpose and intention in this treatise is to persuade, as far as lies in me, by these sure and infallible grounds, all such good Christian readers as bear not only, the naked name of a Christian but kythe ["mainfest"] the fruits thereof in their daily form of life to keep their hearts and hands free from such monstrous and unnatural rebellions whensoever the wickedness of a prince shall procure the same at God's hands; that, when it shall please God to cast such scourges of princes and instruments of his fury, in the fire, ye may stand up with clean hands and unspotted consciences, having proved yourselves in all your actions true Christians toward God, and dutiful subjects towards your king, having remitted the judgment and punishment of all his wrongs to Him, whom to only of right it appertains. "To persuade the

|

But craving at God, and hoping that God shall continue his blessing with us in not sending such fearful desolation, I heartily wish our king's behavior so to be, and continue among us, as our God in earth and loving father, endued with such properties as I described a king in the first part of this treatise. And that ye (my dear countrymen and charitable readers) may press by all means to procure the prosperity and welfare of your king, that as he must on the one part think nil his earthly felicity, and happiness grounded upon your weal, caring more for himself for your sake than for his own, thinking himself only ordained for your weal, such holy and happy, emulation may arise betwixt him and you as his care for your quietness and your care for his honor and preservation may in all your actions daily. strive together, that the land may think themselves blessed with such a king, and the king may think himself most happy, in ruling over so loving and obedient subjects. "Our kings be as

|

But when he addressed Parliament again in March,1610, after years of strife and in dire need of money, James changed his tack. Allowing that every king who is not a tyrant will voluntarily submit to the laws of the land, he maintained nonetheless that kings were above the laws, invested by God with absolute sovereignty and absolute in their right to their thrones.

|

KING JAMES I, "A SPEECH TO THE LORDS AND COMMONS OF THE PARLIAMENT AT WHITEHALL"

|

The state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon earth. For kings are not only God's lieutenants upon earth, and sit upon God's throne, but even by God Himself they are called gods. There be three principal similitudes that illustrate the state of monarchy: one taken out of the word of God, and the two other out of the grounds of policy and philosophy. In the Scriptures kings are called gods, and so their power after a certain relation compared to the divine power. Kings are also compared to fathers of families, for a king is truly Parens patriae ['father of the country"], the politic father of his people. And lastly, kings are compared to the head of this microcosm of the body of man. "Even by God Himself Kings are justly called gods, for that they exercise a manner or resemblance of divine power upon earth. For if you will consider the attributes to God, you shall see how they agree in the person of a king. God hath power to create, or destroy, make, or unmake at His pleasure, to give life, or send death, to judge all, and to be judged nor accountable to none; to raise low things, and to make high things low at His pleasure, and to God are both soul and body due. And the like power have kings: they make and unmake their subjects; they have power of raising, and casting down; of life, and of death; judges over all their subjects and in all causes, and yet accomptable to none but God only. They have power to exalt low things, and abase high things, and make of their subjects like men at the chess, a pawn to take a bishop or a knight, and to cry up ['praise"] or down any of their subjects, as they do their money. And to the king is due both the affection of the soul, and the service of the body of his subjects. . . . "Kings exercise As for the father of a family, they had of old under the law of nature Patriam potestatem ["fatherly power"], which was Potestatem vitae & necis ["power of life and death"], over their children or family (I mean such fathers of families as were the lineal heirs of those families whereof kings did originally come). For kings had their first original from them, who planted and spread themselves in colonies through the world. Now a father may dispose of his inheritance to his children at his pleasure: yea, even disinherit the eldest upon just occasions, and prefer the youngest, according to his liking: make them beggers, or rich at his pleasure; restrain, or banish out of his presence, as he finds them give cause of offense, or restore them in favor again with the penitent sinner. So may the king deal with his subjects.